Thank you, Matt, for initiating this incredibly important discussion. The proposal for a “disbursal with issuance” treasury mechanism might be a truly practical approach to one of the most persistent challenges in decentralized governance.

Since this is “completely new territory” with “no reference implementation,” I thought it might be valuable to explore the mechanics of this proposal through a more formal lens. I’ve attempted to use a simplified game theory model to analyze its potential impacts.

Please note, this is just a preliminary and simplified analysis intended to provide a theoretical framework and spark further, more detailed research. The real world is far more complex, but I hope this model can serve as a useful starting point.

The Framework: Modeling Participant Behavior

To analyze any economic system, we need to understand how rational actors behave within it. Let’s define a simple model with two key participants:

- The Proposer (P): A developer or team seeking funds for a project.

- The Representative Voter (V): An abstraction for any CKB holder who votes. We assume their goal is to maximize the long-term value of their holdings (as the economic man hypothesis).

And some core variables:

- V_e: The intrinsic value of the Nervos ecosystem (tech, community, network effects).

- S: The total supply of CKB.

- P_{ckb}: The price of CKB, which we can model as being proportional to ecosystem value and inversely proportional to supply. For simplicity: P_{ckb} = \alpha \frac{V_e}{S} (where α is a market sentiment factor).

- C_v: The cost (time, effort) for a voter to research and cast a vote.

- \Delta V_e: The value a given proposal is expected to add to the ecosystem. A great proposal has a high \Delta V_e > 0, while a low-quality or rent-seeking proposal has \Delta V_e \le 0.

- I_{treasury}: The maximum CKB available from the treasury in a given issuance cycle.

Model 1: The Traditional Accumulation Treasury

First, let’s model the default scenario: a treasury that accumulates funds over time. In this model, the secondary issuance (I_{sec}) happens regardless of governance outcomes. If no proposals are approved, the funds simply pile up.

A Voter’s Utility Calculation:

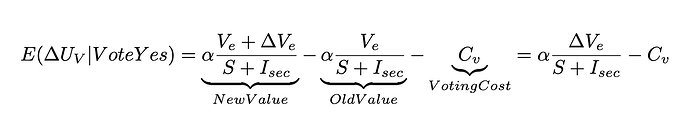

When deciding to vote ‘Yes’ on a proposal, a rational voter assesses their expected change in utility. Their calculation looks like this:

Equilibrium Analysis & The Inherent Flaw:

This model leads to a predictable and dangerous equilibrium:

- Voter Apathy as a Dominant Strategy: If a proposal is bad (\Delta V_e \le 0), a voter has no direct incentive to spend C_v to vote ‘No’. They only avoid a loss, which feels less compelling. If they are unsure about the proposal, or believe their single vote won’t matter, the most rational choice is to do nothing and save the cost C_v.

- The Perfect Environment for Rent-Seeking: Because voters are rationally apathetic, a proposer with a bad proposal (\Delta V_e \le 0) only needs to convince a small, concentrated group of voters to pass it. The cost of the bad decision (a less valuable ecosystem) is socialized across all holders, while the profit is privatized by the proposer. The large, accumulating pot of CKB becomes a massive honeypot that incentivizes this exact behavior, as you mentioned.

Model 2: Disbursal with Issuance Treasury

Now, let’s analyze the burn unused model. The game changes completely because the total supply, S, is no longer a fixed outcome. It becomes an endogenous variable—its change depends directly on the result of the vote.

A Voter’s New Utility Calculation:

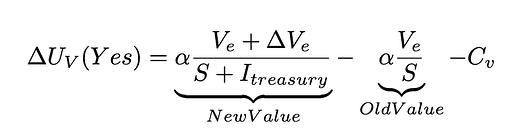

-

If the proposal passes (Vote Yes): The ecosystem gains value \Delta V_e, but the total supply also inflates by I_{treasury}.

-

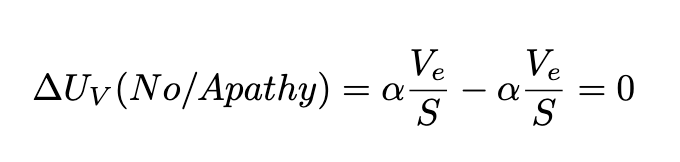

If the proposal fails (Vote No or Be Apathetic): The ecosystem value is unchanged, but critically, the total supply also remains unchanged. The CKB that would have gone to the treasury is never issued. This creates a deflationary pressure relative to the alternative.

Equilibrium Analysis: Why This Mechanism is Effective

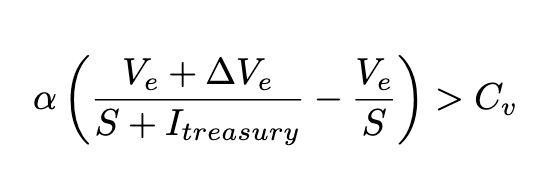

A rational voter will now only vote ‘Yes’ if the utility of doing so is greater than the utility of inaction. That is, if \Delta U_V(\text{Yes}) > 0. This gives us the core decision inequality:

This single formula beautifully demonstrates the elegance of your proposal:

- It Inherently Kills Rent-Seeking: Look what happens if a proposal is rent-seeking (\Delta V_e \le 0). The term in the parenthesis will be negative. No rational CKB holder, not even a whale, would vote to simultaneously decrease the ecosystem’s value AND inflate their own holdings. It aligns incentives perfectly and makes such proposals economically irrational to support.

- It Breaks Apathy for Good Proposals: Voters are no longer just voting on a proposal; they are choosing between two distinct economic futures: a) a slightly more inflationary with more ecosystem value, or b) a less inflationary with stagnant ecosystem value. This forces a clear economic trade-off, providing a powerful incentive to overcome the cost of voting (C_v) for proposals with a genuinely high \Delta V_e.

The Hidden Risk: The “Deflationary Trap” Equilibrium

However, this model doesn’t fully eliminate risk—it transforms it. The new risk is not the misuse of funds, but the absence of their use.

Consider the decision inequality again. What if the community struggles to produce or identify proposals where the expected value (\Delta V_e) is high enough to overcome the perceived cost of inflation and the effort of voting (C_v)?

In this scenario, the rational choice for voters would be to consistently do nothing, letting proposals fail. The system would then settle into a “deflationary trap” equilibrium:

- No proposals are funded.

- The CKB supply grows at the minimum possible rate.

- The price of CKB might remain stable or even rise due to this relative scarcity.

- But the ecosystem itself stagnates. No funding for core development, research, or growth initiatives.

I figure this could be seen as a “pathological” form of deflation born from inactivity, not from a thriving, efficient ecosystem. It also could create a bias against high-risk, high-reward innovative projects whose \Delta V_e is hard to quantify, in favor of the certainty of “no inflation.”

Conclusion

This preliminary analysis suggests your proposal is a powerful solution to the honeypot problem, but its success hinges on avoiding the “deflationary trap.”

My simple model might point toward ways we could further refine this mechanism. Based on the inequality, there are two clear levers we can pull to make the system more robust:

- Decrease the Cost of Governance (C_v): The model shows that a high C_v is a direct barrier to action. We could explore mechanisms to lower this cost for active and valuable contributors.

- Better Framing of Proposal Value (\Delta V_e): The model treats all proposals as having a single, universal \Delta V_e. In reality, the value of a core protocol upgrade is different from a marketing campaign. Perhaps the treasury could be divided into distinct categories (e.g., Core Infrastructure, Ecosystem Grants, Community Bounties) with different evaluation criteria or even different approval thresholds. This would prevent high-risk, long-term research from being judged by the same short-term metrics as other projects, helping to avoid across-the-board voter conservatism.

In conclusion, your valuable insight is a significant step forward. Thanks again for opening up this vital conversation.

Best,