In my last post, I highlighted some of CKB’s unique advantages when it comes to flexibility. But I also see an ongoing UX challenge we shouldn’t overlook: how users understand address changes.

The following article (also posted on Cryptape Jungle) unpacks how the same key on CKB can generate different addresses depending on whether you use type hash or data hash. This isn’t just a technical detail – it goes straight to user trust.

Introduction

In the previous article, we explored how CKB employs a dual script referencing mechanism, utilizing either a data hash or a type hash, to provide users with greater autonomy and control over their interactions with Scripts. This flexibility empowers users to choose between fixed Scripts or upgradable Scripts, depending on their trust preferences.

However, this design comes with a tradeoff: it can produce inconsistent wallet addresses—even when interacting with the same Script.

For many users, especially those who entered Web3 through MetaMask, this feels unintuitive. MetaMask and similar wallets have shaped a mental model where:

One account = one address, and that address never changes.

On CKB, things work differently. An address isn’t static — it’s the product of two factors:

-

Which Lock Script is used, each of which defines a different way to verify ownership and thus produces a different address.

-

How that Lock Script is referenced, which can still change the address even when the Lock Script itself stays the same.

In this article, we focus on the second factor — the subtler case where you keep the same Lock Script, but switching the reference method changes your address.

We will explore:

-

Why data hash vs. type hash impacts address consistency.

-

How this breaks common UX expectations.

-

And how we might redesign wallet experiences to support identity, clarity, and trust—without giving up flexibility.

The Hidden Cost Breaks UX Expectation

As UX designers, we know that consistency matters. Consistency is more than just a design principle—it’s a trust signal. When users see the same patterns repeat, they feel reassured. Consistency conveys professionalism, and it quietly tells users “You’re in control. Everything is working as expected.”

This is especially true when it comes to something as sensitive as a wallet address. In most wallets—especially MetaMask—users are trained to believe:

-

One account = one address

-

That address is stable

-

If the address ever changes, it means something’s broken

So when a CKB wallet generates a different address for the same Script, simply because the reference method changes behind the scenes, that subtle technical detail breaks a deeply ingrained expectation.

From the user’s perspective, nothing changed. But from the system’s perspective, everything did. And that disconnect leads to friction. Users may pause and wonder:

-

“Why is my address different now?”

-

“Did I lose access to my previous funds?”

-

“How do I switch back to my previous address?”

Even though CKB’s design is intentional—and even powerful in terms of autonomy—its surface behavior can feel inconsistent to users. And inconsistency, especially around identities and money, creates doubt. Left unaddressed, that doubt can erode trust. But this isn’t a call to remove flexibility. It’s a call to design better experiences—ones that explain or soften the invisible complexity, so the system feels stable even when it’s dynamic.

Two Moments Where Inconsistency Hurts Most

In this section, I explore two common scenarios where address inconsistency surfaces—and offer design opportunities to help users feel safe and in control.

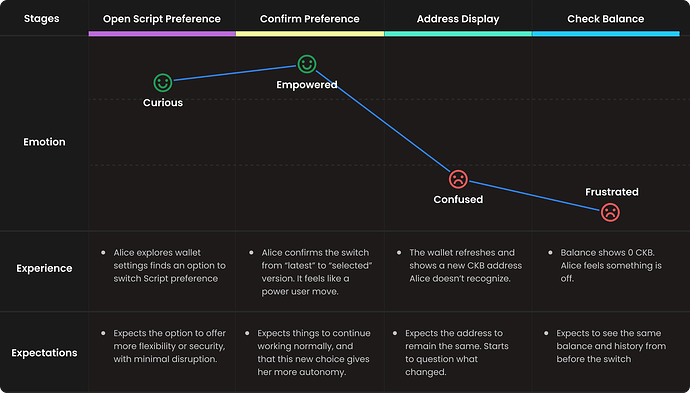

Scenario 1: Switching Script Preference (e.g., Type → Data)

Let’s say a user, Alice, opens her wallet settings and switches her Script preference from “latest” (type hash) to a manually selected version (data hash), opting into a frozen, immutable version of the logic. Suddenly, her address changes.

Even though Alice still controls the same wallet, the experience is disorienting.

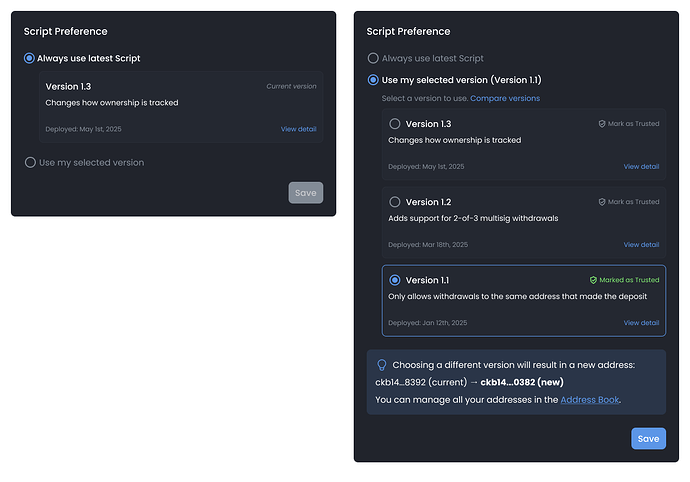

Design Opportunity 1: Let Users Preview the Change Before It Happens

Problem: Users may be surprised by an address change after switching the Script preference.

Solution: Show a preview of the resulting address before confirming the switch.

Why it works: When users change the Script preference, their address changes—but without upfront context, this can feel like a bug. Previewing the resulting address helps users set accurate expectations, reducing confusion and reinforcing that the system is transparent and predictable.

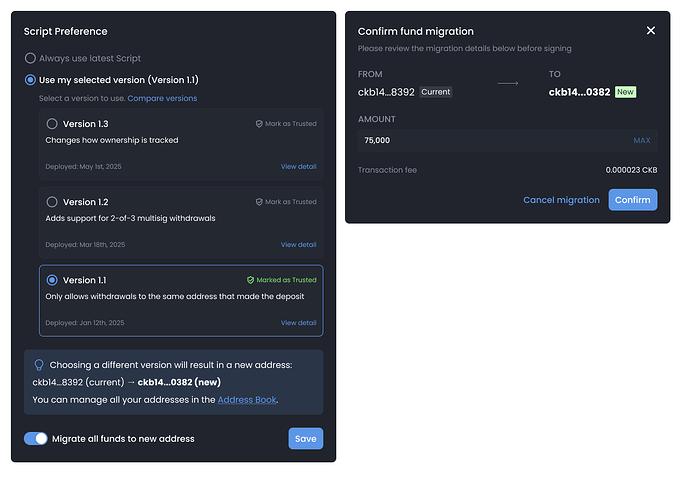

Design Opportunity 2: Offer Seamless Fund Migration

Problem: Users may feel uncertain about the safety or accessibility of their previous funds.

Solution: Include a one-click “Migrate Funds” option after switching.

Why it works: Instead of asking users to detect, understand, and manually transfer funds from their old address, the system can offer a clear shortcut. A “Migrate Funds” button provides reassurance and convenience. It turns what could be a confusing manual task—identifying which funds are still in old addresses, constructing a transaction, checking fees—into a single clear action. This proactive design reinforces the idea that the wallet understands the user’s intent and handles the complexity behind the scenes. It also builds trust by showing that no funds are ever lost—just split across script contexts that the wallet manages on the user’s behalf. By embedding this support right after the address switch, users feel guided, not abandoned.

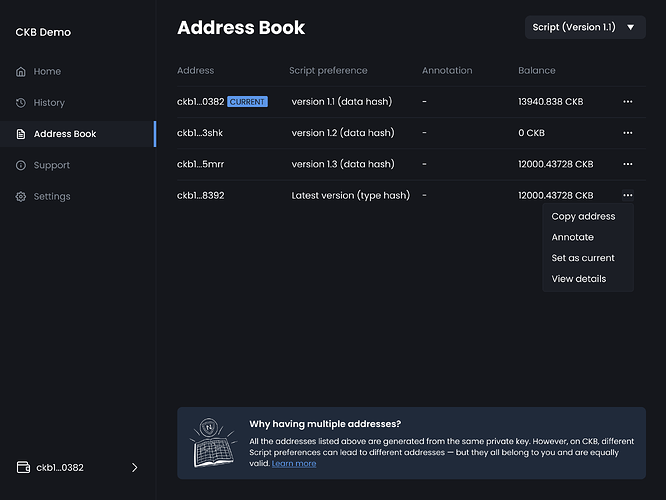

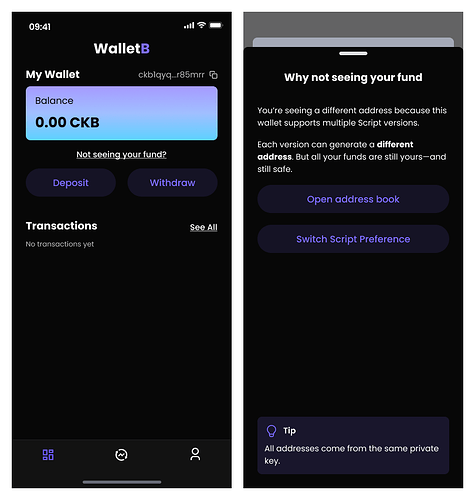

Design Opportunity 3: Create a Manage Addresses Page

Problem: Users don’t have visibility into which addresses are tied to which Script.

Solution: Provide a centralized “Address Book” that shows:

-

All addresses linked to the wallet

-

The Script preference used (e.g., latest version or a specific version)

Why it works: Listing all wallet-associated addresses and the Script tied to each restores transparency and puts users back in control. Letting users view, label, and even reactivate previous addresses reinforces the idea that nothing is lost, and that they can undo or revisit changes when needed.

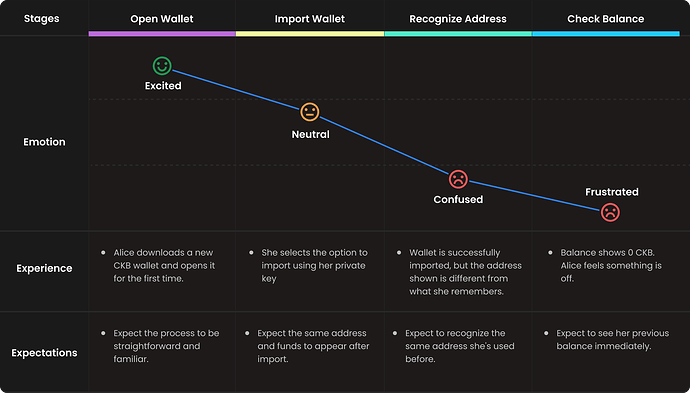

Scenario 2: Importing a Wallet, Seeing a Different Address

Imagine Alice has been using a CKB wallet where her address was derived using the data hash reference method. One day, she installs a new wallet app on a different device and chooses to import her existing wallet using her private key.

The process is smooth—until the wallet finishes setting up and presents a different address. Her balance reads 0 CKB.

At this point, Alice feels confused and concerned:

-

“Did I use the wrong key?”

-

“Why is this address different?”

-

“Where are my funds?”

From a technical perspective, nothing went wrong. The new wallet might used a different Script reference method (e.g., type hash) when generating her address. But Alice doesn’t know that—and the product isn’t helping her understand it either.

What we’re seeing here is a disconnect not between key and ownership, but between context and clarity.

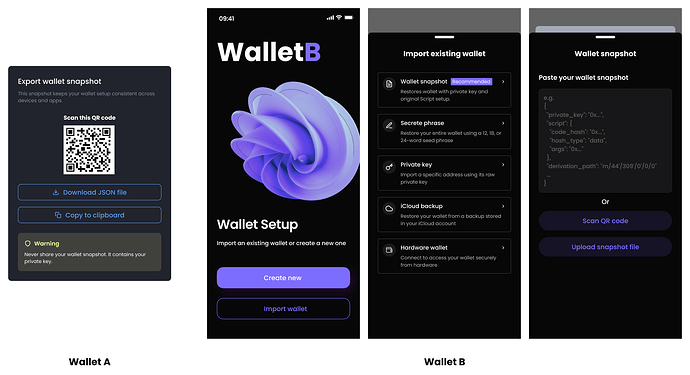

Design Opportunity 1: Carry Context, Not Just the Key

Problem: Private keys alone don’t preserve the setup that created the original address.

Solution: Introduce a Wallet Snapshot Export, which includes:

-

the private key

-

the Script reference type (data or type hash)

-

optional metadata like wallet name and derivation path

This way, when Alice imports her wallet into a new app, the system can either:

-

restore her previous setup exactly, or

-

notify her if there’s a mismatch, giving her the chance to resolve it.

Why it works: This approach embodies recognition over recall — one of the core usability heuristics. Instead of forcing users to remember how their original wallet was configured, we let the system recognize and restore it automatically. By embedding Script context directly into the exported snapshot, we reduce cognitive load and eliminate setup ambiguity.

It also supports user control and freedom. When the system can either recreate the original configuration or notify users of mismatches, it proactively helps users make informed decisions without panic.

Most importantly, it’s a form of minimalist design. We don’t surface every technical detail upfront — we make the smart defaults work behind the scenes, preserving trust through subtle but meaningful guidance.

Design Opportunity 2: Help at Zero Balance

Problem: Seeing “0 CKB” can make users assume their funds are gone.

Solution: Place a contextual help link next to the balance area: “Not seeing your funds?”

Why it works: This nudge doesn’t interrupt the flow—but it works because it meets users exactly where confusion arises. When Alice sees “0 CKB” after importing her wallet, she might panic, thinking something broke. A small, well-placed message like “Not seeing your funds?” doesn’t treat this as an error—it simply validates her instinct and offers a next step. It helps her recognize that the situation is understandable, not alarming. Instead of requiring her to dig through support articles or navigate complex documentation, the system embeds reassurance directly next to the balance. That kind of in-the-moment guidance feels intuitive and responsive—it clears up uncertainty before it turns into doubt, all without asking the user to understand how script references work behind the scenes. It’s just enough help, exactly when and where it’s needed.

Conclusion

Trust isn’t built solely on transparent code or thorough documentation—it’s also built through experience.

As UX designers, our job is to simplify complexity without compromising user confidence. We can design wallets that feel transparent, stable, and trustworthy through just-in-time explanations, proactive export formats, thoughtful UI nudges, and beyond.

The flexibility that CKB offers at the protocol level is a strength—not a liability. It shouldn’t be sacrificed. Instead, it’s our responsibility to wrap that flexibility in interfaces that foster clarity and control, so users feel empowered, not overwhelmed.

In the end, trust is not just about what the system does. It’s about how the user feels.

References

The more I think about it, the more I realize: the real problem isn’t the inconsistency itself. It’s the mental model — many users still assume address = account. On CKB, it’s actually: one account can link to many addresses.

If we can shift toward this mental model, then address changes stop feeling like bugs and start feeling natural. This is why I believe identity abstraction — separating account from address — is an important step forward for CKB.

Curious what others think: how can we help guide users toward this shift?